Making full and immediate open access a reality: the role of the institutional OA policy

This is the text of a presentation that Chris Banks gave to the OASPA 2019 Conference.

Overview

I’d like to thank the organisers for accepting what I acknowledged when submitting it, was rather a cheeky proposal which sees me standing here today talking to an association of Open Access Scholarly Publishers about the role of an institutional open access policy in fulfilling cOAlition S’s aim of “making full and immediate open access a reality”. A “green” policy.

Here’s why:

- Researchers are keen not to see their choice of publication venue restricted as a result of funder OA mandates, and many disciplines and individuals are only at the early stages of any move away from venue of publication as a proxy for quality

- Institutions and funders don’t want and cannot afford that choice to be retained at any expense

- Publishers are keen to retain and grow their author base and don’t want to lose any authors as a result of changing funder mandates.

- Publishers, some, because of size and/or complexity of portfolio, see a transition to OA as challenging on a global scale

And then:

- Funders want to see more of the research they have funded immediately OA, but not at the expense of ever escalating costs

- Newer entrants to OA publishing need funding, time and space to explore new business models

- Learned societies, particularly those who have outsourced their publishing activities, struggle to understand business models, and may not yet have alternative service suppliers available to them.

Have we made progress?

- The UK, through the Wellcome Trust and the Finch review, have been driving open access to the outcomes of the research that they have funded.

- Slide: RCUK analysis

- The Finch report in 2012, has resulted in Research Councils UK allocating block grants to institutions to enable more strategic support for open access publishing. Over £70m has been allocated but the sought-for transition to OA publishing has not happened.

- Instead, our researchers have seen a plethora of policies, from funders to publishers which I have described as the “policy stack”.

cOAlition S and Plan S

Then, along comes cOAlition S – a significant and growing group of research funders which, judging by Plan S aims, are immensely frustrated with the stalled transition, and are seeking to accelerate the transition but not at any cost.

Plan S should create the much sought for level playing field for funder Open Access policies. But at best, it should act as the lever to drive transformation and innovation in open access publishing. For the latter to happen, a LOT needs to change.

Here’s the bit that I can influence. It comes from the perspective of a research-intensive institution where maintaining researcher choice and constraining costs are key to supporting that transition, particularly if we want to enable support for publishing innovation and OA infrastructure.

This is where a Model Institutional Open Access Policy comes in to play:

- it can support researchers when publishers cannot yet, or will not move away from paywalling content – my data suggests many journals will struggle to transition

- it will support research intensive institutions in prioritising spend and constraining costs during that transition

- and it will leave the option open to divert funds to support innovation.

The model is not new: it is the Harvard model open access policy adopted by 76 institutions across the globe. We have worked to make it applicable in the UK where a different copyright regime is in play. Our solution – the UKSCL Model Institutional Open Access Policy – now sits ready and waiting as an enabler of the Plan S aim to make “full and immediate open access a reality”.

Yes, it is a green policy. I stand here in front of a group of publishers to assure you that whilst I don’t believe that the future should or will be “green” OA, nonetheless repositories, supported by institutional open access policies are an essential part of the transition, particularly for research-intensive institutions like my own.

The UKSCL was originally conceived to smooth policy complexity. It was called a “licence” because our original proposal was to deploy a “decaying licence” which, over time, would resolve to CC BY for self-archived materials. Whilst a solution that struck a balance between publisher & funder policies, it was deemed too complex by the community. Personally, I believe it could still have a role in balancing competing concerns around Plan S implementation. Another discussion.

Implications for research intensive institutions

Some argue that there are enough funds in the system to support a transition

- Schimmer, Geschuhn & Vogler state “The current library acquisition budgets are the ultimate reservoir for enabling the transformation without financial or other risks” and we’ve heard that restated during our conference.

- Whilst this may technically be true, as with feeding the world, putting in place the necessary protocols to turn it into a reality becomes a significant challenge. Particularly when the supportive measures – in our case, funding from research funders – is likely to be limited both in scale and in terms of where it can be spent, from 2024.

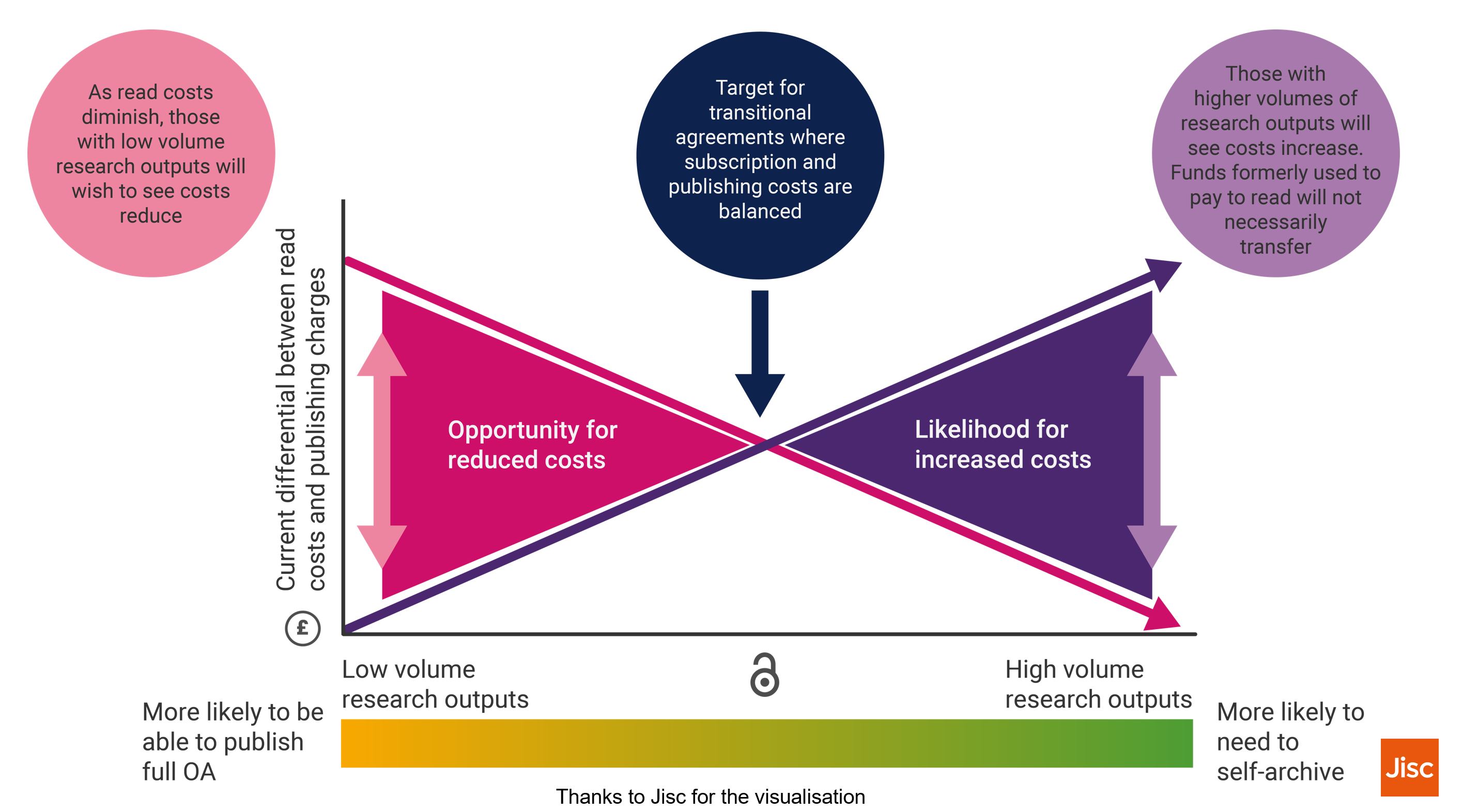

Here is my conceptualisation of what would play out if the only thing that were to change were the funder mandates. It is not to scale!

- Across the X axis: the teaching intensive to the research intensive institutions

- The y axis shows prices to read dropping as more becomes open access, and prices to publish rising according to research intensivity. There is a sweetspot where the effect on an institution’s budget is negligible

- The irony in the UK is that whilst the current mix of policies stand, expenditure across our consortia means that with our subscriptions funding, there probably is enough in the system to support Read & Publish deals. As cOAlition S membership expands, though, this quickly starts shifting the scenario to the right where the only means by which research-intensive institutions can ensure alignment with funder aims will be to self-archive. Hence our need for a legal mechanism to do so – the UKSCL Model institutional open access policy – while we negotiate with publishers.

None of us want this as a longer term outcome but all of us need to change something if it isn’t to become embedded as the norm, including.

- Expectations that the per-article income for some larger publishers must drop

- Noting that income isn’t necessarily just derived from subscriptions. If accompanied by moves towards efficient and effective processes on both sides then there are significant efficiencies to be gained.

How the policy will be implemented, and to which outputs will it apply?

- In the UK, we are awaiting the outcome of the UKRI Open Access review and once known, the final terms of the UKSCL Model Institutional Open Access Policy will be re-written to align with that policy

- Depending on the implementation date of the UKRI policy, we may have a transition period during which the model policy is adopted but where academics might be able to choose a more restrictive licence. This, we know, would support those who feel that a ND licence is appropriate for their discipline.

- Task and finish groups are currently working on advocacy and operationalisation

Recipe for adopting the model policy elsewhere

Having undertaken the process of making the Harvard model work in the UK, I’m happy to share the recipe with others. In short, it involved academic consultation, making the policy work within the UK legal © and iP framework, and ensuring that institutional policies and practices were aligned. At all stages we engaged legal © and IP input.

Incentivisation through policy

Policy should incentivise. In the case of the UKSCL model institutional open access policy there are:

- Incentives for the academic: the retention of academic freedom to publish in the venue of choice knowing that rights have legally been retained in order to meet funder open access aims

- Incentives for the library and finance directors: reassurance that funder mandates are not accompanied by significant new financial burdens for the institution

- And finally, incentives for publishers: to work with us so that an affordable transition can be achieved, and so that it is the Version of Record which is freely and publicly available on publication.

Finally, If I were to have one wish, it would be this: that, having done all this work to establish this legal approach to solving first, the OA policy stack, and now, the challenges for implementing cOAlition S aims, that the policy was not, in the end, needed, and that we were instead able to find an affordable and workable route to full and immediate open access.

Chris Banks

September 2019